This text follows Discovering Hilma af Klint: Part One from April 4, 2025.

In 1891, Hilma af Klint’s spirit guides sent her a life-changing directive: “Hilma will receive a great gift if she never forgets the power of the highest.” Having trained as a painter, and having used drawing to ‘receive’ mystical messages in her Spiritualist groups, the artist decided to offer her practice as a conduit for the will of her higher beings for the next fifty years. “The images are painted directly through me, without preliminary sketches, [and] with great force,” she wrote.

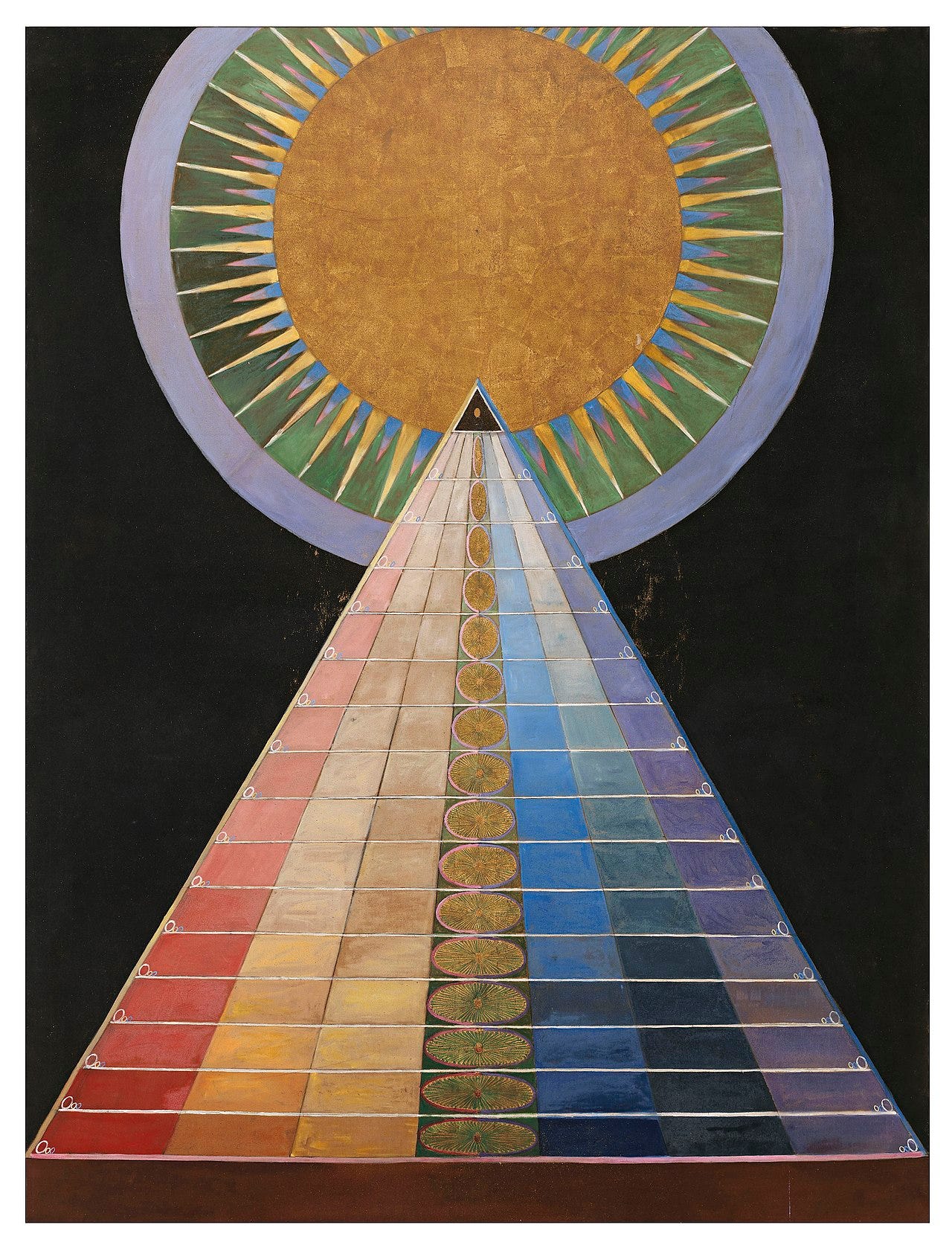

The largest spirit commission came in late 1907, when af Klint completed “The Ten Largest” in just two months of frenzied work. Each enormous canvases measures more than 3 by 2 meters and is filled with mysterious symbols that resemble text, flowers, and reproductive forms. I was fortunate to see the series in its entirety at the artist’s Bilbao exhibition earlier this year, where the works’ impressive scale inspired a sense of reverence, while their brilliant colors and freewheeling forms radiated a sense of vitality and joy.

Af Klint initially considered herself to be a medium for spirits, but as she shifted from esoteric Christianity to even less conventional beliefs — and as she became ever more immersed in her spiritual world — she eventually saw herself as a gifted mystic who could remember past lives, experience visions, converse with the dead, predict the future, and employ healing powers. What af Klint came to believe is connected to alternative religious currents of the time, especially Anthroposophy, a movement that she was greatly invested in. However, it also appears that the artist’s spirituality was unique to af Klint herself; her beliefs shaped and were shaped by her own life and art practice.

At no point does Julia Voss, the author of Hilma af Klint: A Biography, question or pathologize af Klint’s dynamic and all-consuming spiritual life. Transmissions from spirits that the artist recorded in her notebooks are quoted as if they come from letters sent by a living human, for example. A modern reader — especially one without a religious background of any kind — may find this bewildering, so Voss spends a great deal of time in the book detailing the complex metaphysical movements developing in af Klint’s orbit, including figures like Rudolph Steiner, who af Klint saw as a spiritual leader and visited numerous times.

But Voss is also careful to consider women’s position in Sweden and Europe in af Klint’s day. Though the artist was one of the first female students to attend Stockholm’s Royal Academy, she and other Swedish women wouldn't gain the right to vote in their country until 1921, when af Klint was nearly 60. Voss also discusses the rise in mental hospitals alongside women’s struggles for liberation, and pays tribute to Sigrid Hjertén, an avant-garde painter and contemporary of af Klint who was institutionalized and later died from a botched lobotomy in 1948.

Clearly, the stakes were high for women like af Klint who defied established social norms. Besides her unconventional spiritual beliefs, she remained a working artist, never married, and seems to have been engaged in romantic relationships with women throughout her life. Nobody painted the way that Af Klint did, certainly, but also very few lived openly the way she did, either.

Perhaps this was also why she delved so deeply into her elaborate spiritual world, where the strictures and prejudices of the day didn’t matter. And despite the lack of commercial success or wider recognition for her paintings, her spirit guides always seemed to cheer the artist on when she needed it. After she completed “The Ten Largest,” for example, af Klint’s spirit guides were pleased, telling her, “You’ve now completed such glorious work that you would fall to your knees if you understood it.”

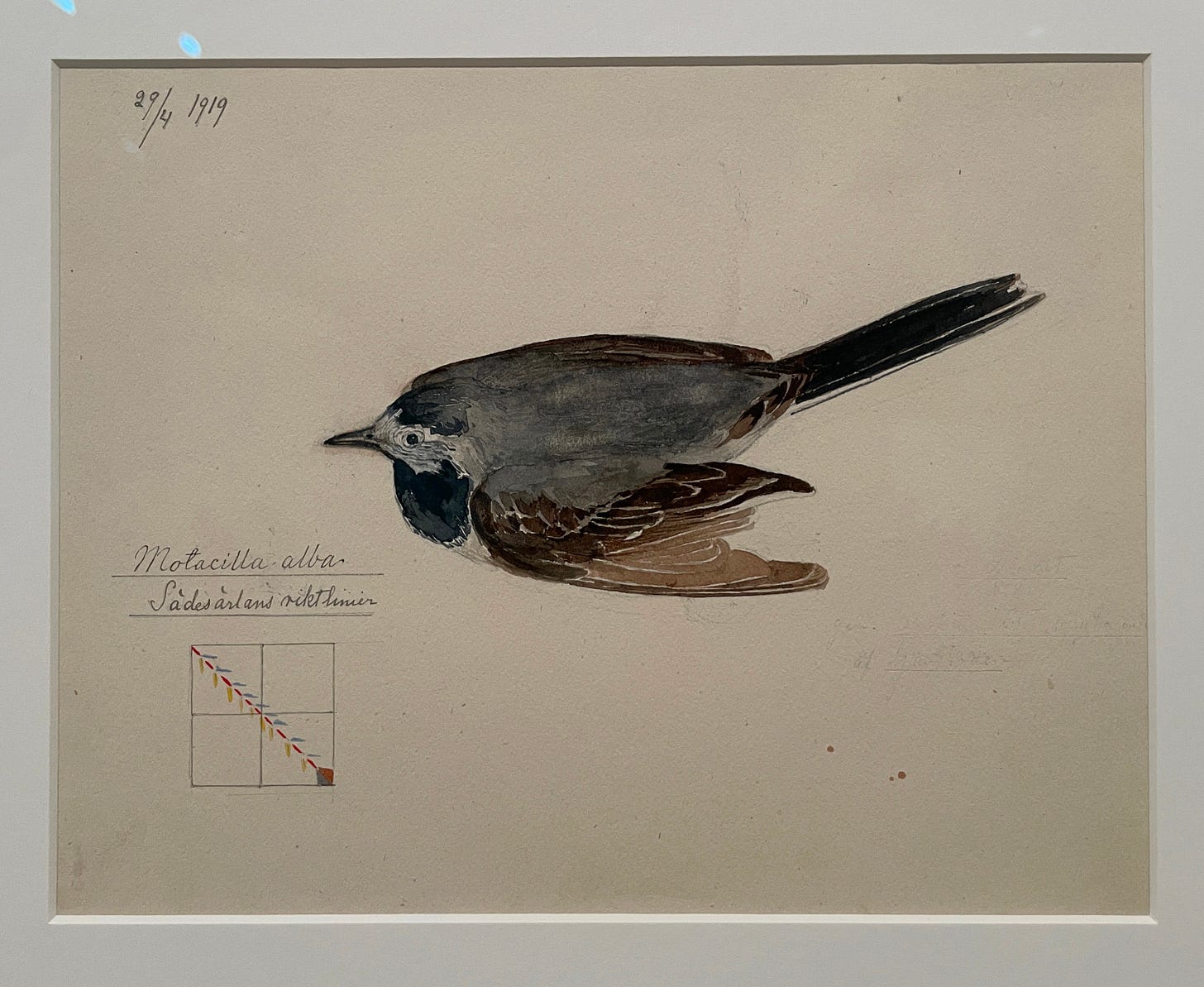

And that was a major and ongoing issue: af Klint seems to have not fully ever known what to make of the work she created. This was not for lack of trying: she wrote thousands of pages of notes and theories, and meticulously cataloged and sorted her output throughout her life. Af Klint’s paintings were not formal experiments or records of momentary feelings. The artist was convinced that the work had meaning, and that its message was vital to humankind. But the pieces that she made continued to elude her, perhaps until the very end.

The last entry in af Klint’s extensive notebooks, written just days before her death in October 1944, states: “You have service to the mysteries before you and will soon understand what is required of you.” Perhaps the cryptic message means that af Klint would fully comprehend her work only in the space after death.

Af Klint was largely ignored from most of the 20th century, and she remains misunderstood and mysterious today. Voss’s book sheds light on af Klint’s spirituality, which is what the artist considered to be the most important and animating factor in her life and work. At a time when it’s uncertain whether her paintings will continue to be displayed publicly, it’s illuminating to learn about af Klint’s deepest convictions in this book.

Very interesting artist