In September of 1943, Hilma af Klint received an offer that most artists would see as heaven-sent. Three years earlier, the Swedish artist, author, and activist Tyra Kleen had visited af Klint’s studio on the island of Munsö and been impressed by what she saw. Now Kleen wanted to use her family fortune to move af Klint’s entire artistic oeuvre into a new, custom-built museum dedicated solely to preserving and displaying it for posterity. Kleen also promised to provide af Klint with a nearby home, studio, and unlimited medical care — all for free — for the rest of the artist’s life.

Af Klint was 80 years old when she received Kleen’s letter, and in principle it couldn’t have arrived at a better time. Af Klint had spent the past four decades developing a pioneering and highly personal form of abstraction, but neither the contemporary art world nor her beloved spiritual circles seemed to care for or understand her work. Still, she’d pressed on, telling Stockholm’s Anthroposophical Society in 1937 that “My desire for the work which began in 1907 and is still ongoing to come into good hands is what keeps me physically alive.”

With Kleen, af Klint finally seemed to have the chance to present her complex vision to the world. In fact, the artist had long dreamed of building what she referred to as a temple to house her entire creative history. And yet, af Klint responded to Kleen’s offer with an unequivocal no: “It was unfortunate that despite your interest in what I produced,” she said, “you still didn’t understand its higher origins.”

Those higher origins were largely defined by a series of spiritual beings who the artist had been in contact with since her teenage years, and who regularly ‘spoke’ to af Klint in her many notebooks. “The children of the world will scorn your work,” they warned the artist at the time. “You will be derided by them, but that is better than becoming famous for earthly success.”

Af Klint and her spiritual advisors knew that her work was ahead of its time, and the artist stipulated that it be kept private until 20 years after her death in 1944. In fact, it took much longer for af Klint’s art works and writings to reach to the wider public, and significant institutional support and scholarship have come only in the past few years.

A major sign of official art world arrival came with af Klint’s recent retrospective at the Guggenheim in Bilbao, Spain, which I was fortunate to catch before it closed on February 2. I’ve been a fan of af Klint’s paintings since I first saw them in a book about 20 years ago, but I’d never experienced them in person. On my quick trip to Bilbao, I spent most of my time at the museum. I left the show entranced but perplexed; af Klint’s exhibition felt very different from most others I’d seen. I left with questions about the paintings’ imagery and meaning, and I wondered about the woman behind such vibrant but enigmatic work.

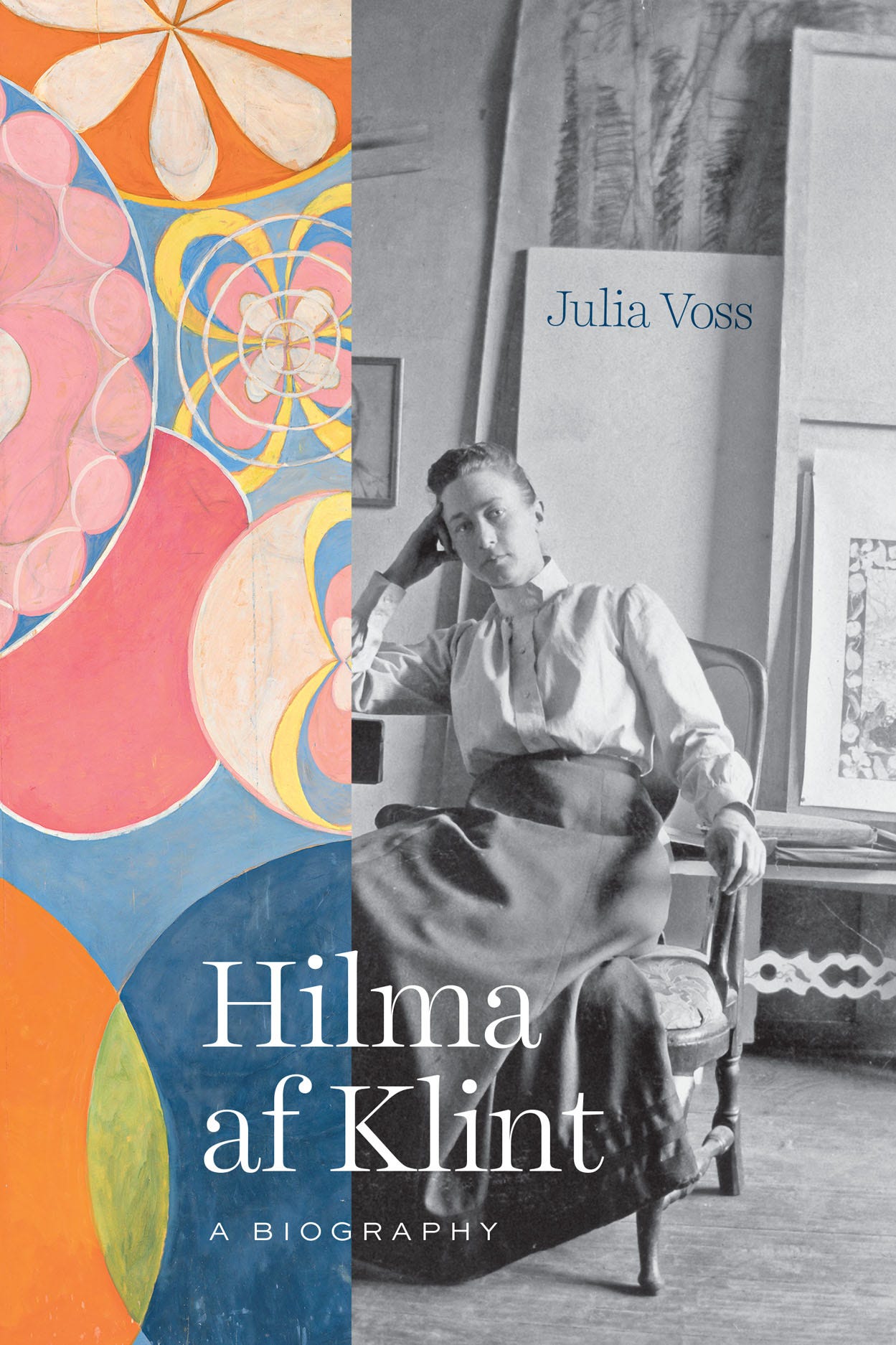

And so I was very happy to find Hilma af Klint: A Biography by Julia Voss. The recent book takes on the enormous task of both telling this notoriously private artist’s life story while explaining — or at least shedding light on — her expansive art. Voss’s book pulls from af Klint’s full archive, including some 26,000 pages of hand-written, drawn, and typed notebooks. However, very little of this material refers to the artist’s daily life, travel, or relationships with other people. Instead, the notebooks evidence the artist’s all-important, all-encompassing spiritual evolution. They also serve as the site of exchange between af Klint and her guides, which include both esoteric entities known only by single names as well as the dead.

Even though the artist stipulated that the notebooks and other works be sealed for twenty years after her death, they weren’t meant to remain hidden. Af Klint called her work “The Fifth Gospel,” and spent much of her career searching for ways to share it. Accordingly, Voss organizes her book around the artist’s spirituality. We learn that af Klint’s beliefs were both uniquely her own — direct contact with her personal spirit guides informed much of her belief system — and tied to developments in the religious thought and science of her day. After all, af Klint grew up in the age of X-rays, radioactivity, the telephone, and other innovations in which the invisible gained unexpected powers.

The sudden death of af Klint’s younger sister Hermina in 1880 when the artist was in her late teens coincided with her initial plunge into unorthodox beliefs. Af Klint’s activity in Spiritualist circles — where participants attempted to communicate with beings beyond the realm of the living — stretched the bounds of her Protestant upbringing. But these groups also provided a strong sense of community and an outlet for her grief.

Voss writes that af Klint and others like her “shared the experience of loss and the feeling of responsibility that grows out of it. It was for them, the living, to remain vigilant, pen and brush in hand. If there were a crack in reality that could bring them into contact with the beyond, they would find it. And if signs came from higher worlds, in whatever form, they would not fail to register them.” Af Klint’s early experimentations lead to a lifelong obsession with expanding her own and others’ spiritual awareness through her art.

In 1882, af Klint joined the second generation of women to attend Stockholm’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Her paintings there were accomplished but conventional, and she worked as a medical illustrator after graduation. Af Klint’s art remained separate from her spiritual pursuits until 1891, when a life-changing message arrived from the beyond: “Hilma will receive a great gift if she never forgets the power of the highest.”

To be continued in my next post...

What a strange and interesting artist...I can't wait to read more ...