On a Sunday morning in early June, I woke up to find two black-and-white cows grazing quietly outside my window. Cows outnumber people in the Valles Pasiegos, the region in central Cantabria where the Spanish artists Belén Rodríguez and Javier Arce live in a restored shepherd’s cabin surrounded by rolling green hills. The artists invited me to visit their secluded home and studio, where cows and singing birds are their constant companions.

I first met Rodríguez about five years ago, when I wrote about her work for BOMB Magazine. At the time, the artist was making big, bright fabric works streaked and speckled with bleach in a studio on Madrid’s southwest side. The pandemic facilitated Rodríguez’s move from the Spanish capital to the countryside of Cantabria, where Arce had already established himself years before. The change also motivated major shifts in her work: Today the artist’s materials are sourced just steps from her front door, and they are far from chemical.

Nature is now at the center of Rodríguez’s world. A small forest that lies just past her home and garden supplies her with a variety of plants that she uses to dye ochre, rust, and olive hues into her work. Still grounded in textile media, the artist’s inventive and poetic pieces have expanded into installation and performance in recent years. On a morning walk, I asked Rodríguez about her work with the plants nearby, and we talked about the ways that people impact the landscape around them.

Lauren Moya Ford: How did you first start working with plants from the forest?

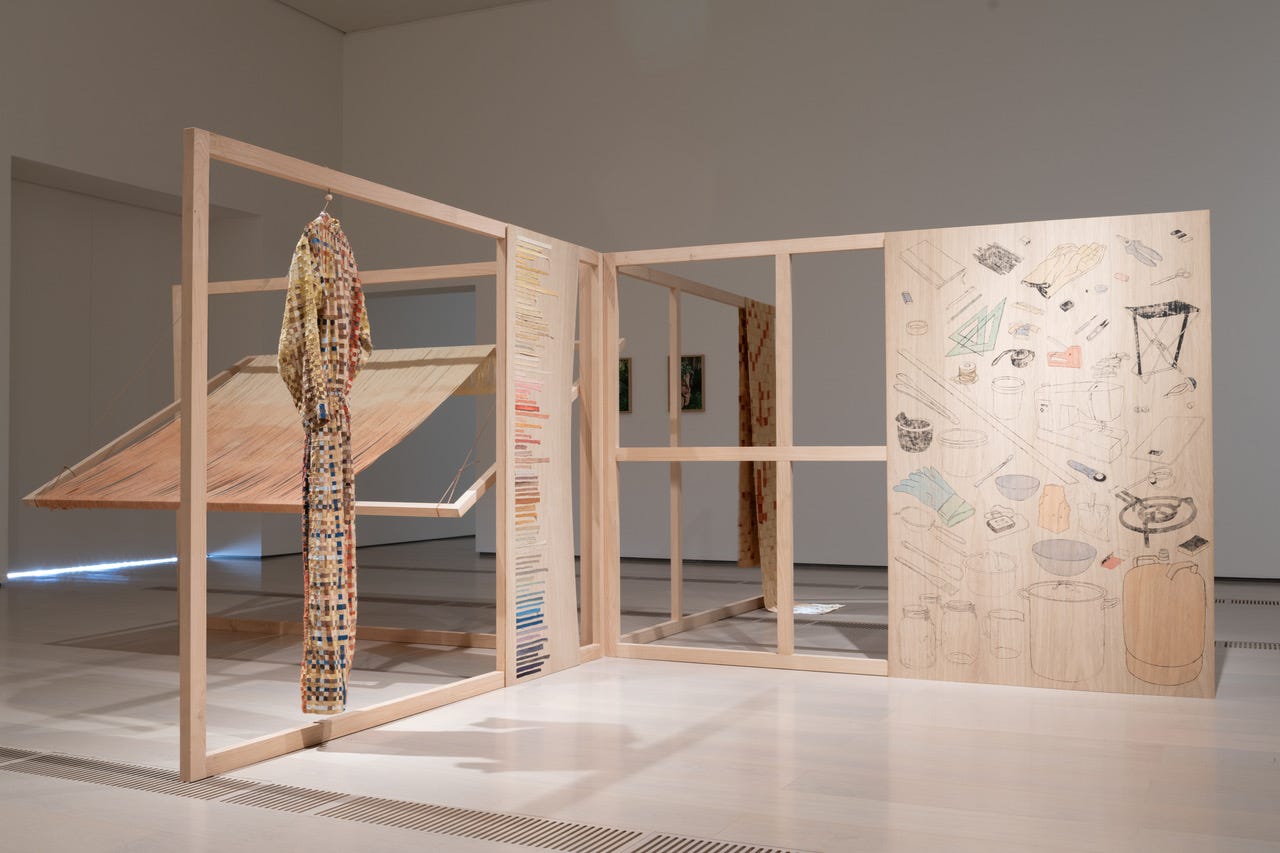

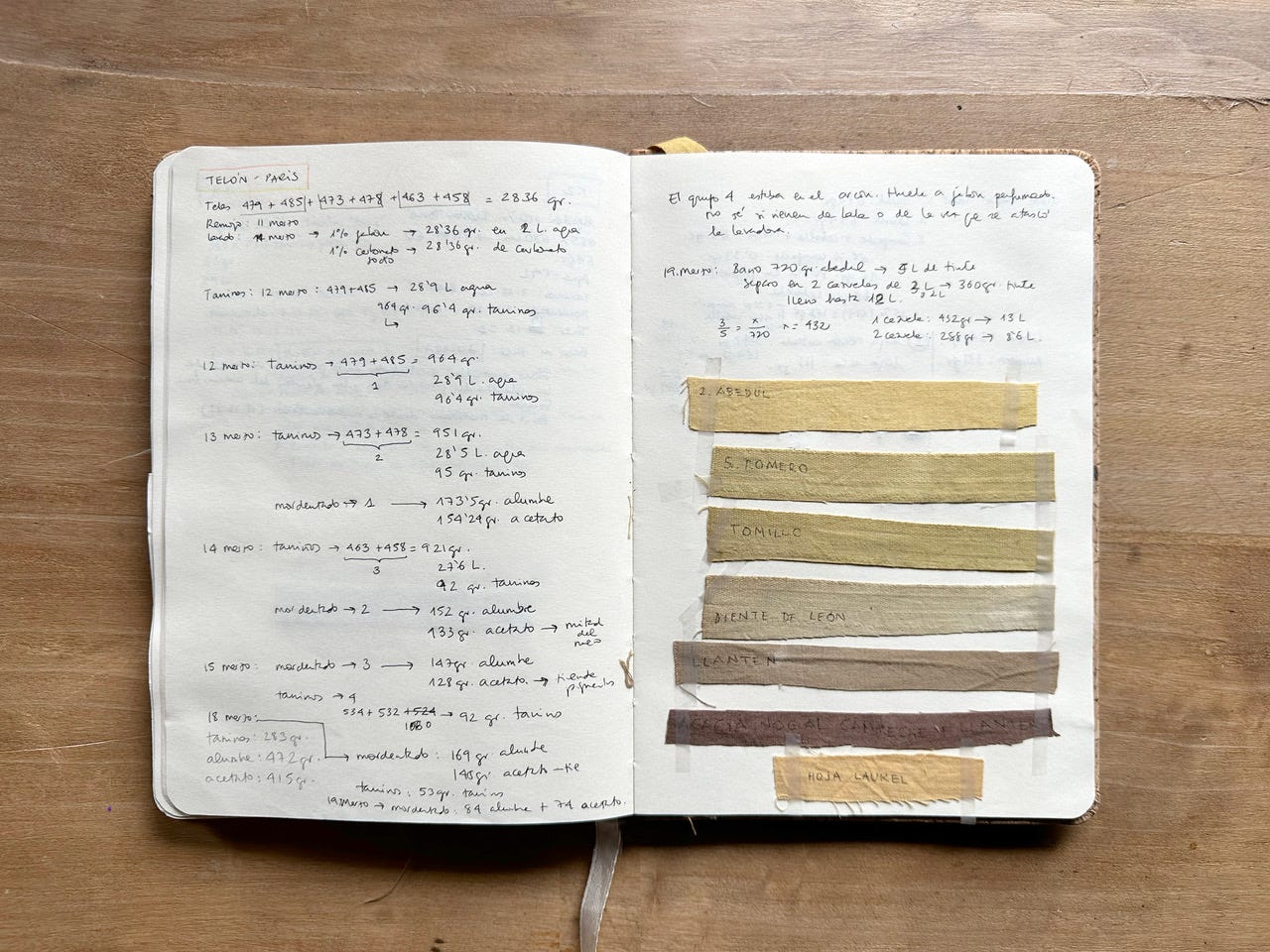

Belén Rodríguez: I was invited by the curator Chus Martínez to produce a new work for an exhibition about the countryside that would be held at the contemporary art center Collegium. At the time, the forest across from our house was for sale, and I knew that the neighbors — there are farmers on both sides — wanted to buy it to expand their pastureland. If that happened, they were going to cut all of the forest’s trees down. I was worried that any day the bulldozers would show up and it would be too late, so, the idea of doing something artistic to buy that forest was floating around in my head. At first I thought about crowdfunding, but then this invitation came and it occurred to me that I could invest all of the money from the exhibition into buying the forest, and that I could make it the protagonist of my work by using its material — that is, the color of its plants — to create a huge piece that would occupy the exhibition space. I didn't know how to dye yet, so I took an intensive course to learn the technique and then spent months collecting leaves, bark, flowers, and weeds to dye different strips of fabric. Each strip was dyed with a plant, and once dyed, I wove them together, creating a sort of representation of that forest. It was very intense work.

LMF: Do you plant things in the forest, or do you only use plants that grow naturally there?

BR: This forest is totally natural. Plants grow on their own here, so it’s not necessary for me to do anything to help them along. Javi and I recently read Por un bosque primario en Europa occidental, a manifesto by the French botanist Francis Hallé about primary forests. The book explains how important it is for there to be old trees and even fallen trees — which also serve a function — in a place like this. Hallé also says that a forest that has been recuperated by man will never really be the same as an untouched older forest that is hundreds or even thousands of years old. There are very few forests that are like that today. One of the few examples is the Białowieża Forest in Poland. But my own forest is very small by comparison.

LMF: How do you know if a plant can be used as a dye?

BR: In reality, everything can produce a tint, but some plants will generate more or less interesting colors. I don’t necessarily care as much about the specific color because I’m more interested in the concept behind the work. When I work with the forest, the final piece is made with that forest. It’s a kind of nature that underlies what you see, and the colors that the plants produce when you use them to dye is actually a different reality. The majority of the colors I create are shades of beige, yellow, and brown, but in the end each one is unique.

LMF: Nowadays we’re so saturated with artificial colors, so when I see colors made with natural dyes from plants it seems like something new and different. It feels like a relief for the eyes.

BR: Exactly. They’re colors that offer a certain kind of refuge. And they’re also so harmonious: Natural colors always look good together.

LMF: Do you have to wait for a certain season or time of day to collect the plants for your dyes?

BR: No, but it’s important to collect the plants while they’re alive. Dried leaves don’t have active ingredients, so they don't work. At the beginning I didn’t know that, so I also tried with plants that had even been burned. [Farmers in the area sometimes set fires to clear unwanted brush from their land]. But they don’t produce any dye. Since I started this major project, I’ve been learning as I go.

LMF: I see quite a few eucalyptus trees growing here. It's a controversial species in Galicia because it isn’t native to the region and it can accelerate wildfires, among other problems. Are you planning to keep the eucalyptus in this forest?

BR: When people make plantations where they only grow eucalyptus, that causes problems because it deteriorates the land. But there’s a rich biodiversity here. We don’t just have eucalyptus growing; there are many other types of trees like chestnuts, oaks, and beeches, and they all grow well together. They find a way to coexist. The problem is when man comes with his arrogance and tries to control the land.

Javier Arce: And it’s not just trees here. We also have deer, wild boars, porcupines, and many other animals. If you enter the forest you’ll find where they sleep and you’ll see them.

BR: Some people may think that the eucalyptus isn’t part of our native vegetation, but how do we determine what’s native? And native since when? Is our idea of native vegetation based on when we began to classify the species that are in this landscape? Before that, there were likely other types of plants. How do we know that before, in the Middle Ages for example, there were these same species of plants here? We don't know that, and the landscape around us has already been thoroughly intervened upon for a long time to create the meadows and pastures used for farming in this area. So we can live with the eucalyptus trees. They’re not harming the land. Here the land is balanced.

Belén Rodríguez’s work is featured in the group exhibition Metabolic Rift at Josh Lilley Gallery in London through August 9, 2025. Interview translation by the author.

I love this story! Thank you for sharing this.