In 1962 at 24 years old, Joel Meyerowitz quit his job as an editor to become a full-time photographer. Inspired by the stark black and white street photography of Robert Frank, Meyerowitz spent his first years snapping scenes around Manhattan with fellow up-and-comers Tod Papageorge, Tony Ray-Jones, and Garry Winogrand. By 1966 Meyerowitz was ready for new horizons and left for Europe. Over the next year he traveled some 30,000 kilometers and took some 25,000 photographs across England, Wales, Scotland, France, Spain, Germany, Turkey, Greece, and Italy.

Arguably the most important destination on the photographer’s decisive journey was Málaga. Between 1966 and 1967, Meyerowitz spent six months in this southern coastal city making photos that convey a deep involvement with Málaga’s rich flamenco culture and its dynamic daily rhythms. “Málaga is a place that changed my life as an artist and as a man,” Meyerowitz said in 2024. Today the artist is known as a pioneer of color and street photography. His time in Europe, and especially his stay in Málaga, was a sort of artistic and personal coming of age.

Some of Meyerowitz’s most compelling and intimate images come from his close relationship with one of Málaga’s most notable flamenco families. When the photographer met the Escalonas, a family of gifted musicians, he brought along his audio recorder. “They had never heard a recording of themselves,” Meyerowitz later recalled. “So my recorder, in a way, allowed them to understand ... the power of their music and the beauty of flamenco.” From then on, Meyerowitz spent his evenings with the Escalonas at their home, photographing their gatherings filled with laughter and music.

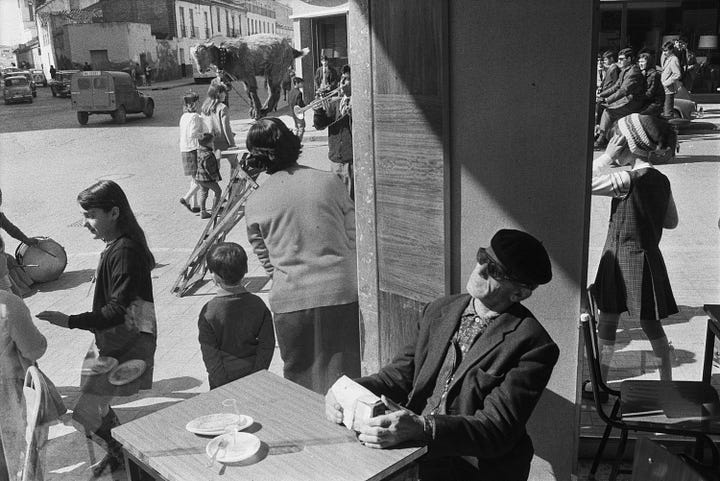

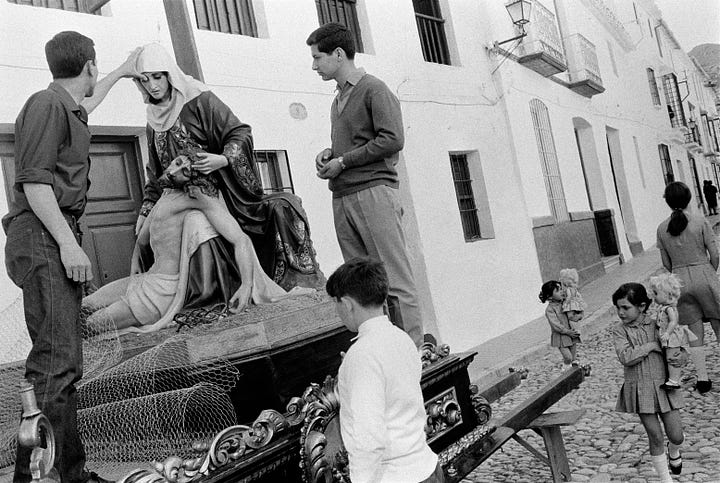

By day, Meyerowitz took to the streets. While his flamenco photos portray the intensity of a single performance, his street scenes capture a multiplicity of unexpected contrasts and parallels. In one image, serenity and chaos clash as a blind man sits peacefully in a café while pedestrians, street performers, motorcycles, cars, and even a dancing goat clamor just outside the window. In another, two men stand with life-sized sculptures of Mary and Jesus as two little girls walk by carrying their dolls. This photo was taken during Holy Week, but Meyerowitz prefers to snap this scene over the high drama and spectacle of the religious parades.

Meyerowitz arrived in Spain at a time when the country was still firmly under the grip of the dictatorship, and his images subtly document the period’s tensions and contradictions. I first came upon his Spanish photographs from the 1960s at a 2019 exhibition in Madrid. One of the pictures that I found notable then (please forgive the poor quality of my phone photos) shows a priest in a long black cassock walking with a group of smiling soldiers. These men represent two of the dictatorship’s core institutions — the church and the military — while a Pepsi-Cola stand nearby signals outside influences. In another photo, three highly-decorated military men lounge on a café terrace as a worker shines one of the official’s boots. The writer Ana Belén García Flores calls these pictures “exceptional documents of an era” that show “the gray Spain of the dictatorship, which is timidly looking toward social transformation.” In these sharply observed street snaps, Meyerowitz seems to question prevailing ideas of tradition and power.

Last week Meyerowitz was named the winner of the 2025 PHotoESPAÑA Prize justbefore his new exhibition Europa 1966-1967, which features photos from his time in Spain and other parts of the continent, opened at the Fernán Gómez Centro Cultural de la Villa in Madrid. Nearly sixty years after his first visit, the 87-year-old artist continues to hold a close connection with Spain.