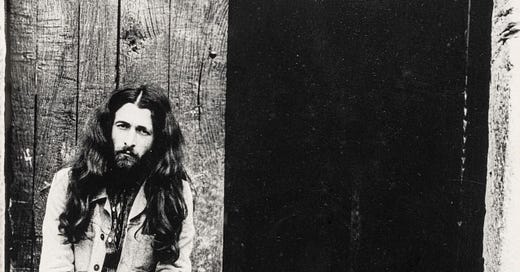

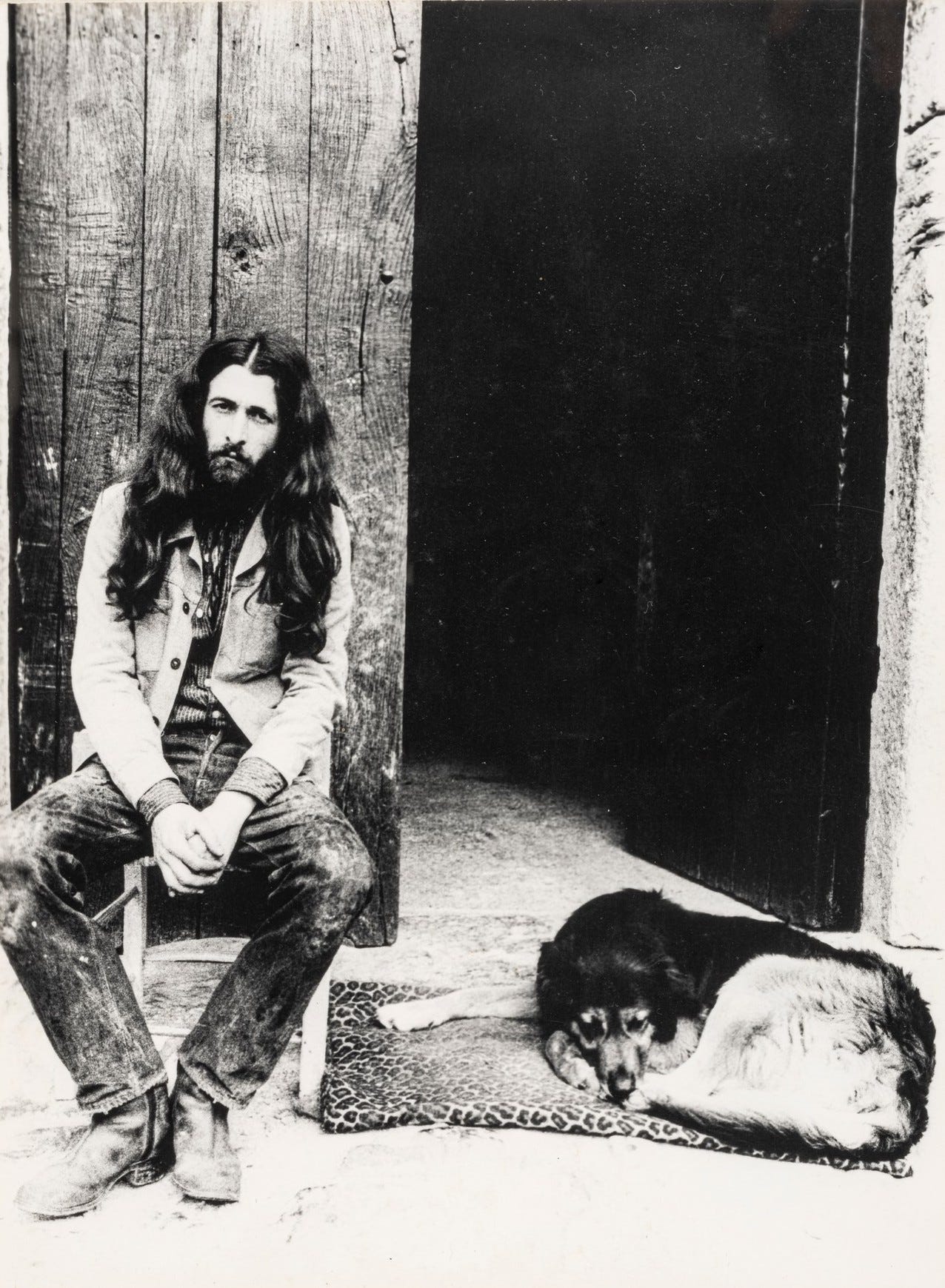

In 1969, Juan Luis Goenaga left the city behind. The 19-year-old had spent the past two years studying art in Madrid, Rome, Barcelona, and Paris, but felt unsatisfied with the education he’d received there. Now that he was ready to strike out on his own, he chose to live and work in Alkiza, a remote town in interior Gipuzkoa on the slopes of Mount Henrio. Far from the major art centers of Europe, Alkiza was the place where Goenaga would establish his own practice and forge a new kind of Basque art.

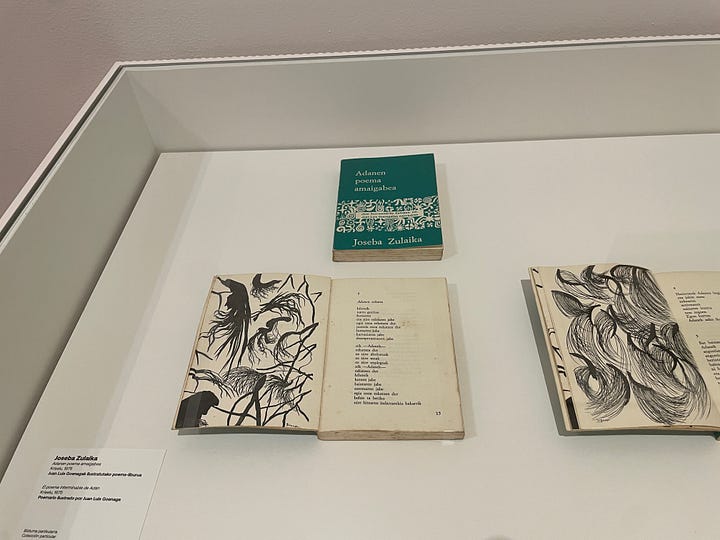

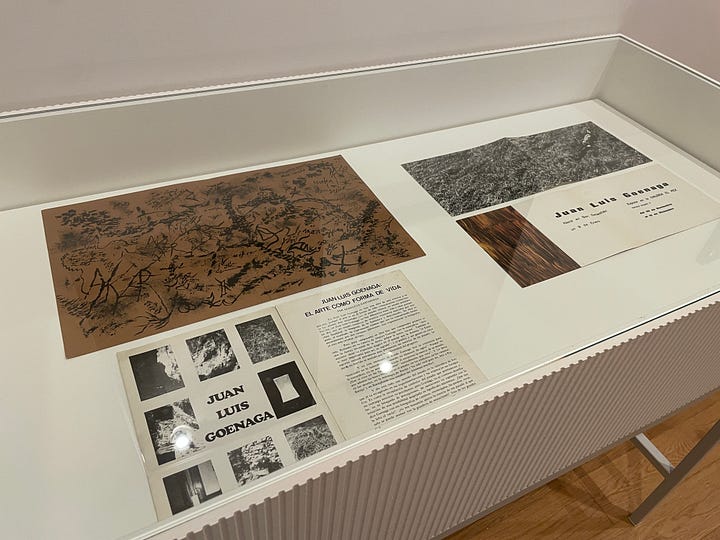

Juan Luis Goenaga. Akiza, 1971–1976 at the Bilbao Museoa is a rare glimpse at this fruitful and foundational period in the artist’s life. Curated by Mikel Lertxundi, the exhibition features some 100 artworks in a stunning variety of methods and materials, including drawings and paintings as well as documentation of Goenaga’s little-known Land Art practice and his experimental photography. Together, the works evidence a young artist’s extraordinary first steps inspired by his isolation in nature.

On the map, Alkiza isn’t too far from Goenaga’s hometown of Donostia, where the artist was born in 1950. But even today the sparsely-populated village remains far removed from urban life, and is still accessible only by narrow, winding roads. When the artist arrived in the early 1970s, Alkiza “was a town at the end of the road that marched to other rhythms and ... marked the boundaries between civilization and chaos, present and past,” Lertxundi writes. In pursuit of a kind of ancestral Basque identity, Goenaga chose to live out his “voluntary exile” in a place that seemed less impacted by the rapid changes of modern times.

Alkiza’s rugged nature became Goenaga’s raw material. Shortly after his move, the artist began to create a series of curious and ephemeral installations in the surrounding landscape using found materials like rocks, sticks, and grass. He documented these interventions, which Lertxundi calls “modern archaic remains,” in black and white photographs organized in pages that resemble a kind of archaeological field study. In a recent tour of the show, the curator explained that the paths and crossroads that repeatedly appear in these images stem from Goenaga’s fascination with Basque prehistory and mythology. Lertxundi noted that paths “are places that have been transited through centuries or millennia, and are places where history makes itself present.”

At the same time, Goenaga’s interventions were on the cutting edge of contemporary art. Lertxundi notes that these works from 1971 coincide with other renowned international Land Artists like Richard Long. It’s uncertain how or why Goenaga developed this modality, but his context was one of relative isolation. And although he didn’t continue working explicitly as a Land Artist after this early period, it clearly influenced the works that would follow. Today Goenaga is known best for his paintings, but his Land Art in the rural Basque Country makes him a pioneer of the genre in Spain, and even predates Catalan artists like Fina Mirelles and Angels Ribé.

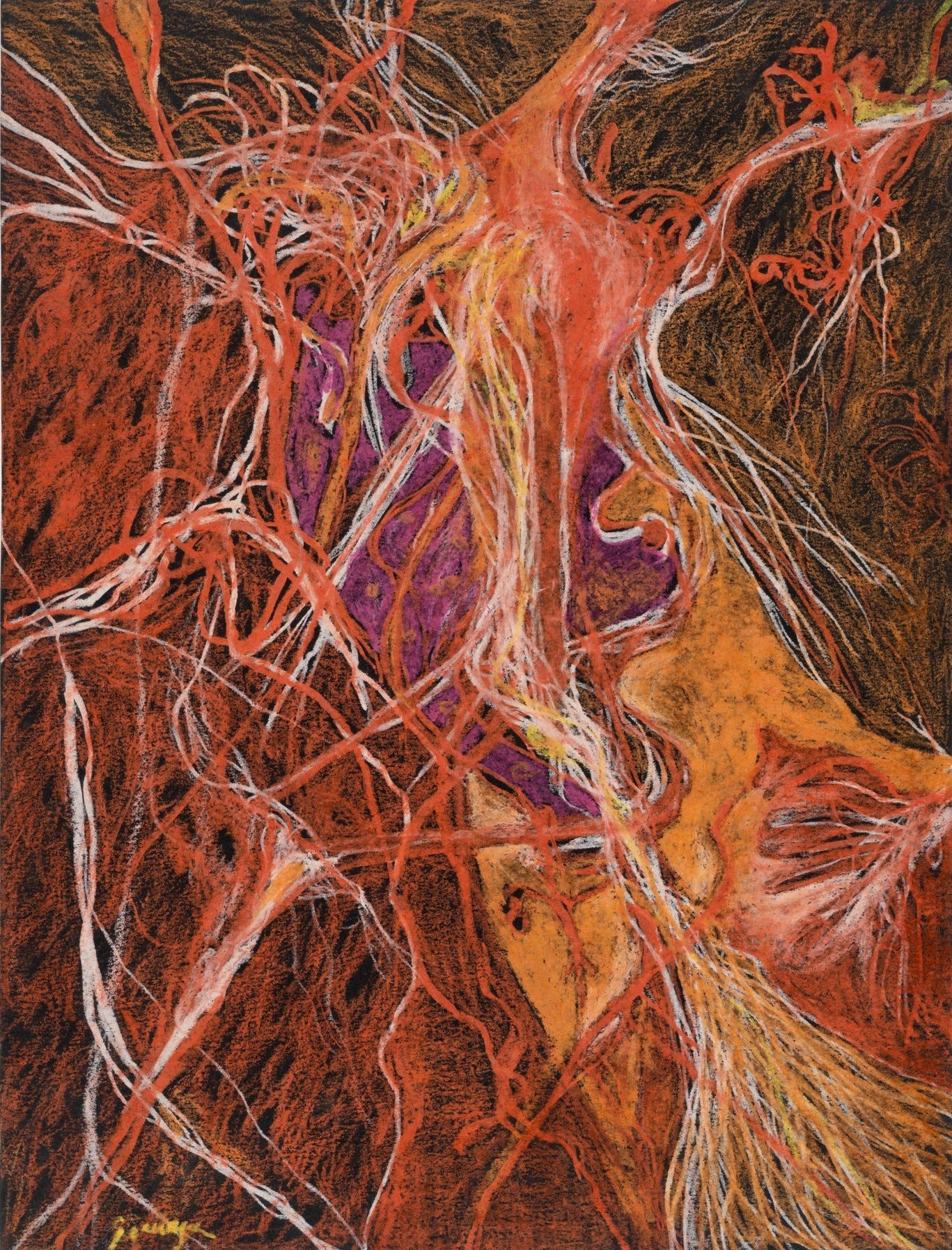

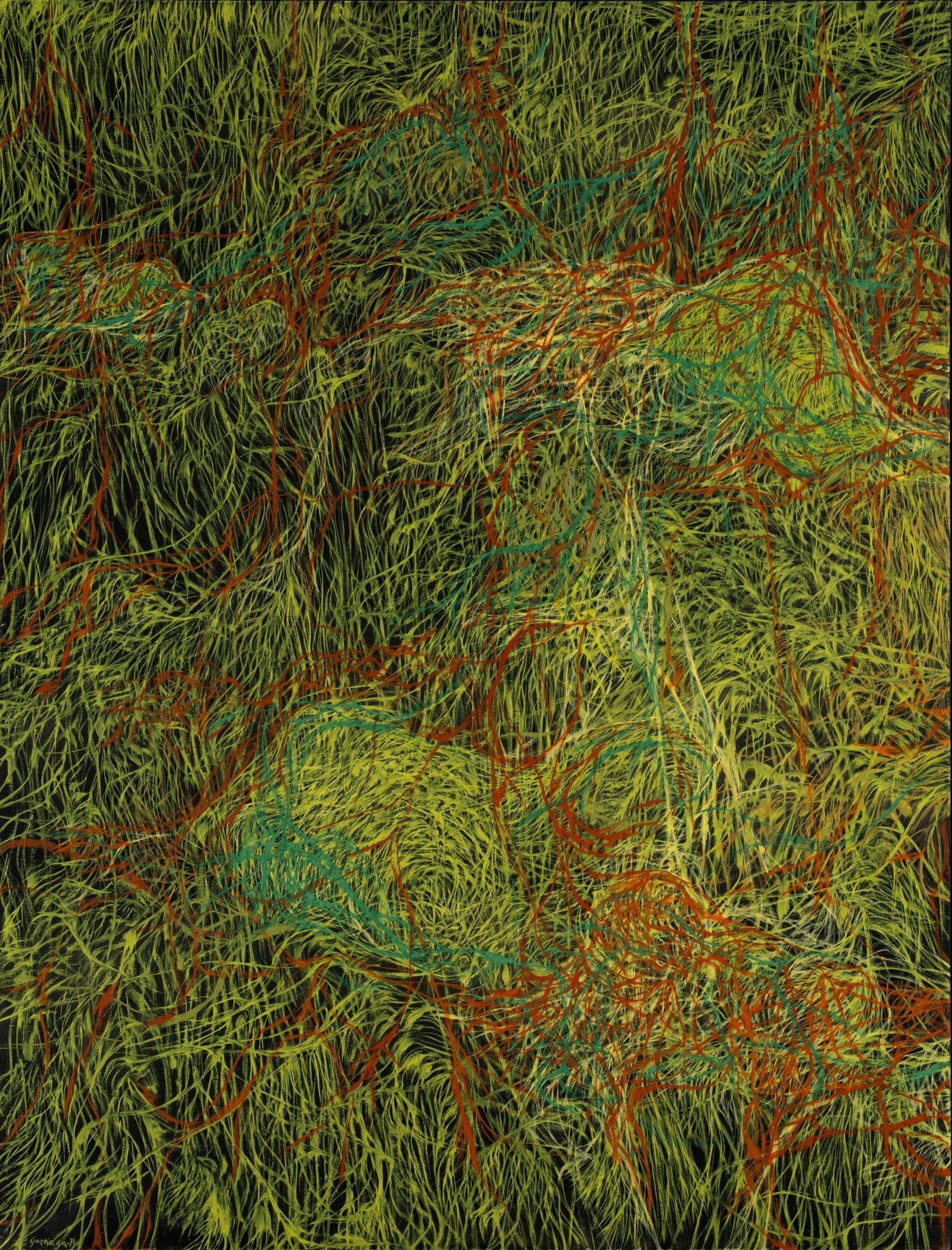

Goenaga spent his days making Land Art outdoors, but his nights were dedicated to painting. These large works are full of dense, energetic strokes of earthy, rich colors. They feature sinuous, shapeshifting networks of knots and swirls that resemble blades of grass, roots, and even neural pathways or constellations. The artist seems to use painting as a means of registering his sensitivities and reactions to nature while enveloping the viewer viscerally. “They are paintings that catch you, demanding that you submerge yourself in them,” Lertxundi observed. The depth of color in these works comes from the fact that the artist made his own paints, an elemental practice that the curator said brought Goenaga into contact with the Earth and with geology.

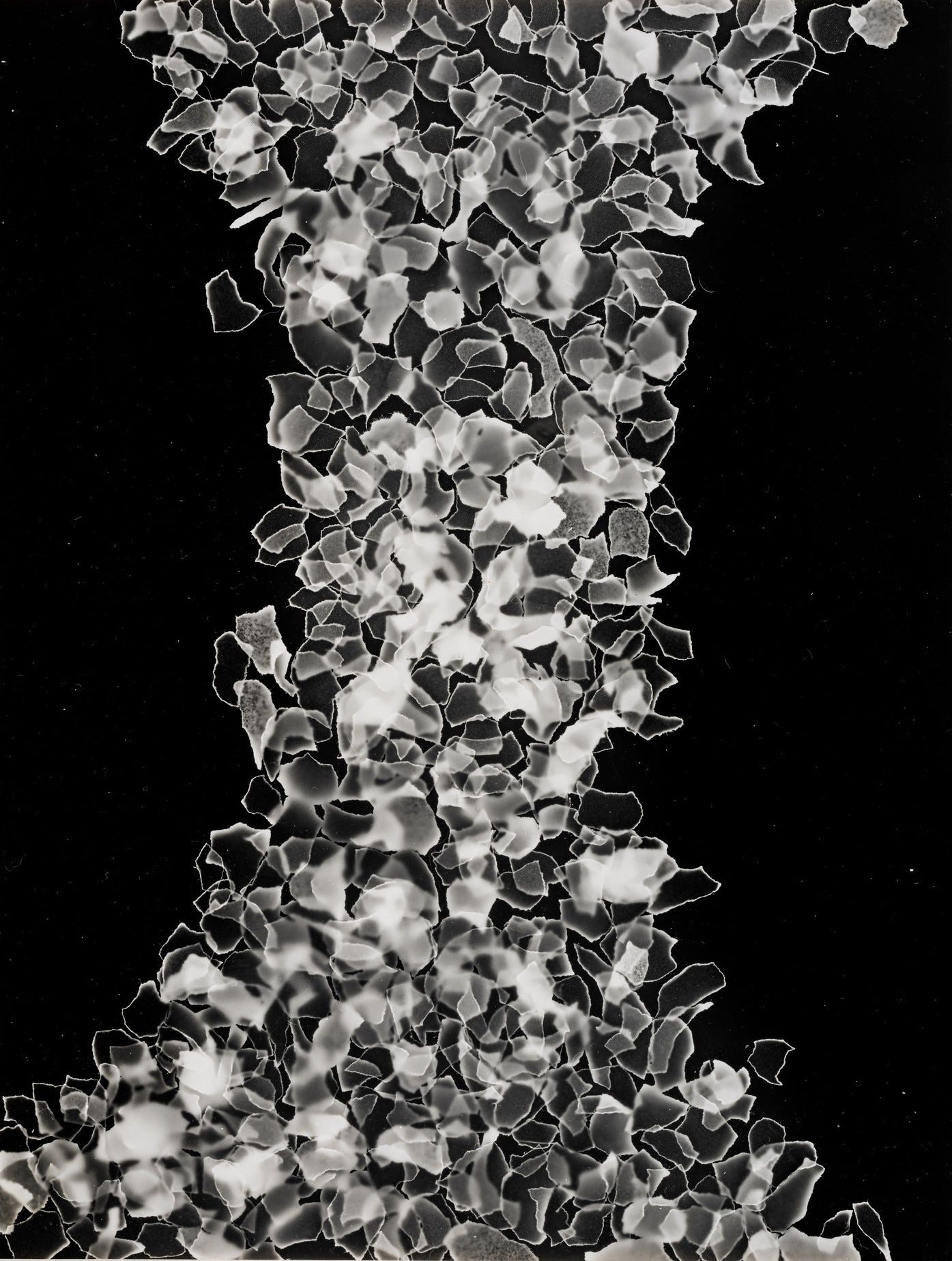

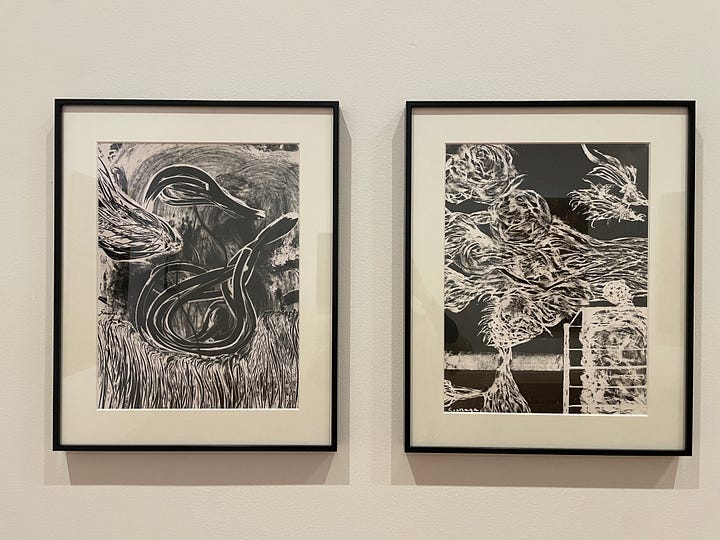

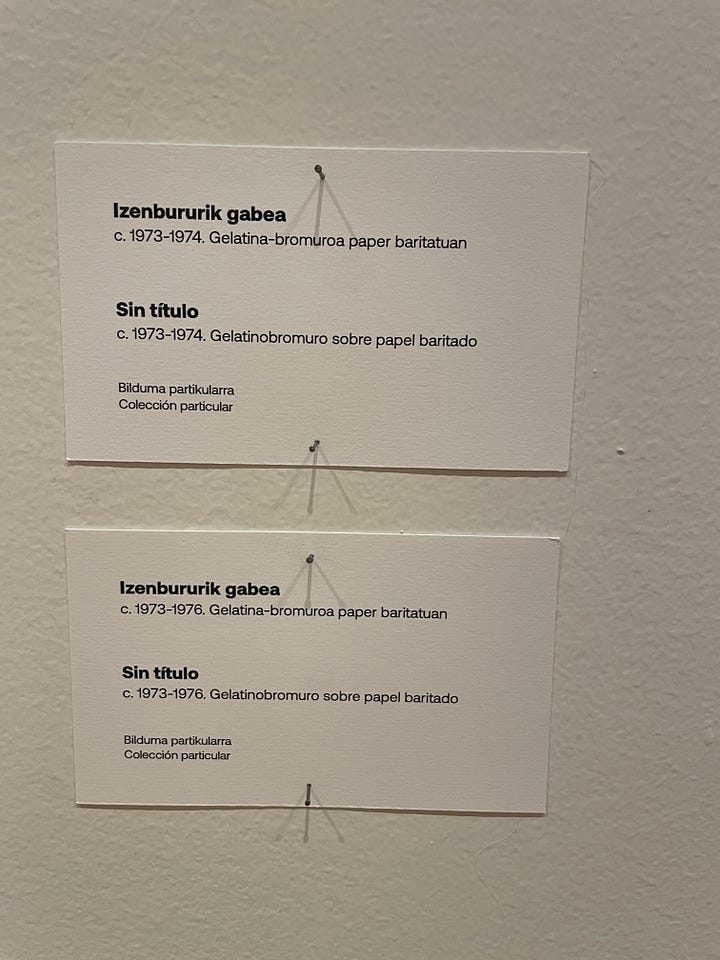

Perhaps the most surprising facet of this period is Goenaga’s photography practice, which spanned beyond documenting his Land Art to more exploratory photograms and gelatin silver prints. As in his Land Art work, these photographic pieces often utilize found natural materials like tufts of sheep’s wool. But these elements are transformed by Goenaga’s experimental photographic processes and stark black and white palette. The artist achieves a striking range of effects here, from painterly, gestural works to mysteriously detailed scenes that resemble an alien organism viewed under a microscope.

By 1977, Goenaga’s life and work took new directions. But he maintained his studio in Alkiza and the years there were formative and fundamental to the trajectory of his career. “From 21 to 26 years old, when others were still training in schools, Goenaga was teaching himself to be an artist,” Lertxundi said. Goenaga continued to be connected to the artistic potential of Alkiza until his death in August of 2024.

Juan Luis Goenaga. Akiza, 1971–1976 was curated by Mikel Lertxundi and is on view at the Bilbao Museoa through March 23, 2025.